The International Protection Office on Lower Mount Street. File photo by Shamim Malekmian.

Sara Althabhaney has lost two cousins to Yemen’s famine. “They passed away because of simple illnesses that are treatable.”

Lack of nutrition undermines the immune system, and sometimes cold and flu turn deadly, said Althabhaney on a Zoom call last week from her home in Ashtown.

While war has played a significant part in creating the famine, climate change has heightened the food-scarcity crisis.

It means crops go thirsty, Althabhaney says. “With famine, people are also starving because certain crops aren’t growing, and there is less supply of water.”

Counts of people uprooted by climate change are often incomplete, ignoring those displaced by the slower symptoms of the global crisis. But the numbers are still staggering.

In 2020 alone, 30.7 million people were displaced by sudden natural disasters such as droughts or floods, worsened by the impact of climate change, according to statistics published by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

And the numbers of displaced are likely to rise. The latest report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that a lack of swift and sweeping global action will translate into deadlier weather events, scorching heatwaves, surging sea levels and less space for crops to flourish.

Yet most countries, including Ireland, don’t consider people displaced by the consequences of climate change as refugees.

Search “climate change” in the database of Ireland’s International Protection Appeals Tribunal (IPAT) – which hears appeals from people who have applied for asylum or subsidiary protection and been refused – and it brings up two cases that centre around the consequences of climate change as a reason for seeking asylum.

Tribunal members rejected both applications, with one expressing doubts about whether climate change is real, and both questioning to what extent it is caused by humans, and even if it were, whether any harm it caused the applicants could be said to have been done to them by a person, intentionally – which they said was legally necessary for the cases to prevail.

A spokesperson for the Department of Justice said that fleeing the consequences of climate change is not an adequate reason for someone to receive “refugee status on the basis of persecution grounds or subsidiary protection status based on the risk of serious harm”.

The United Nations’ Refugee Convention and EU asylum laws used for drawing up Ireland’s International Protection Act 2015 don’t mention climate change, they said.

Not Persecution

When in early 2018 the water ran dry in Cape Town in South Africa, where Bulelani Mfaco’s brother lives, he texted him to say he needed to get out.

“I was here in Dublin when Cape Town ran out of water. I told him you could go back if you want to at a later stage,” he says.

“The option was there for him to go to another province where they don’t have water shortage,” said Mfaco.

Mfaco, an asylum-seeker who is also a PhD student in law at Technological University Dublin (TU Dublin), says he knows that climate refugees don’t fit into definitions under Europe’s current asylum system.

“The law, of course, is silent about people who flee natural disasters because we know that the Geneva Convention doesn’t explicitly offer protection to people who flee on the basis of climate,” says Mfaco.

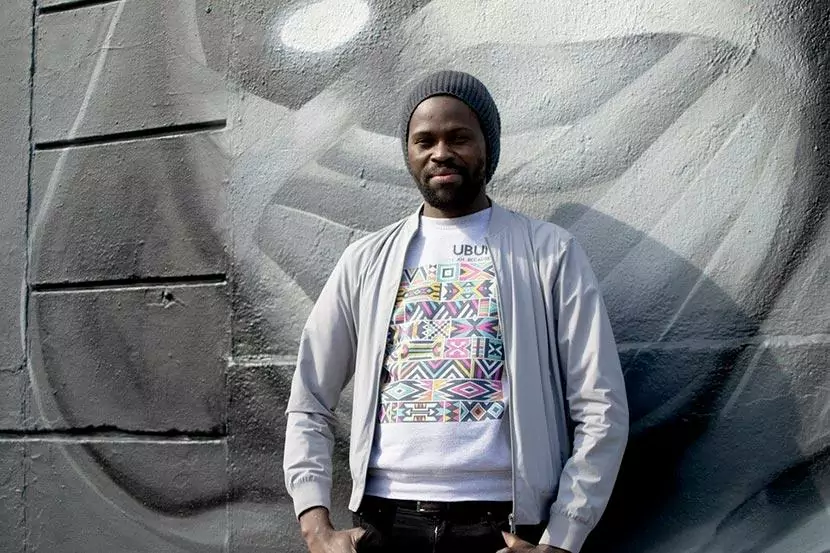

Bulelani Mfaco. Photo by Shamim Malekmian.

Under the UN’s 1951 Refugee Convention, the grounds for seeking refugee status revolve around persecution or discrimination against a person because of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a social group.

Meanwhile, to get the status known as subsidiary protection, people have to be found to be, if returned to their country, at serious risk of harm, such as torture or degrading treatment committed by a state or non-state actor.

In January 2018, Ireland’s IPAT heard the appeal of a man from Malawi, whose village had been destroyed by floods, killing more than 170 people, and leaving the land swampy and uninhabitable.

The man – who was living in Ireland as a student at the time of the floods – told the tribunal that his village was so damaged that nobody could live there anymore.

The government had moved villagers to camps, he said, but they were “disease-prone and generally undesirable places to inhabit”.

The tribunal member who heard the appeal said he accepted that this account of the flooding was true, backed up by media reports at the time.

At issue was whether the man had suffered any persecution or would be at risk of serious harm if he returned to Malawi.

The man’s counsel had said the Malawian government hadn’t done enough to help the villagers, and that that was a form of persecution.

Wrote the tribunal member: “It is a brave but convoluted argument, and has no basis either in law or fact.”

People were getting food and accommodation and camp inmates could come and go freely, he said.

In the tribunal member’s view, the problem was that the conditions in the camp were not to the man’s liking. But inadequacy of state charity isn’t legally the same as persecution or risk of serious harm, he wrote.

Further to the Margins

Between January 2006 to 31 December 2019, not one person fleeing ecological disasters and seeking asylum in Sweden received refugee status, found a recent study on legal attitudes towards climate-change refugees.

In that same window, only one woman managed to win subsidiary protection in relation to environmental factors, says the study by researchers at two human-rights-law institutes in Austria and Sweden.

That wasn’t on climate grounds though, but because “of a clearly established risk of sexual violence in camps in the aftermath of an earthquake in Haiti in 2010”.

During a webinar last week to unveil the study’s findings, Walter Kälin, a constitutional and human-rights lawyer in Switzerland, said the UN’s 1951 Refugee Convention and domestic EU laws fail to consider that natural disasters can prompt persecution and discrimination.

Most people who died during a famine in Somalia in the early 2010s, Kälin said, were “to the very very large extent those belonging to minority clans”.

The environmental crisis is complex and multifaceted and its symptoms, he says, affect marginalised people in a way that counts as discrimination and persecution.

When natural disasters hit, Kälin said, it’s minorities who struggle to access government support.

In October 2019, IPAT heard the case of a man from Bangladesh with diabetes and poor eyesight whose home and land had “succumbed to the effects of climate change” in the early 2010s, lost to floods from a nearby river.

He wanted refuge in Ireland – where he had arrived in 2004 as a student – to be able to work and send money back to his mother in Bangladesh, who was also grappling with diabetes and unable to get insulin for free because of corruption, the document says.

“He says his family had earned a living in the past from crops grown on their land, which has succumbed to flooding, and the credibility of that assertion has been accepted,” says the decision.

He had said his mother might die a slow death if she went without medication if Ireland deported him back to Bangladesh, where the impact of climate change had left the family with no land to farm on, and he feared he would be unable to find a job.

He too could be left without treatment, he said.

IPAT ruled that he did not qualify for either refugee status or subsidiary protection. Because the man wouldn’t be intentionally deprived of healthcare by an actor – as was legally necessary – just failed by the general system and widespread corruption or, as the tribunal member described it, by “naturally-occurring socio-economic deprivation”.

“He appears to be poorly educated and essentially unskilled,” wrote the tribunal member of the applicant.

But he has worked here in Ireland and should be able to find some kind of job there, although probably not one that would pay much, they wrote.

And “if he were required to pay for the necessary medication and treatment”, they said, “there is a reasonable likelihood that he would be unable to pay some or all of the associated costs”.

Natural, or Intentional?

Joy-Tendai Kangere, co-founder of Rooted in Africa and Ireland, says rich countries have exploited the resources of poorer states, inflicting ecological harm for decades, and now refuse to recognise and help those fleeing the results.

“During colonial times, wealthy nations, as we call them, would have come to, you know, the African continent or whichever other continent seeking resources trying to grow their economies,” she says.

There are ecological consequences to that and subsequent generations are paying the price, says Kangere.

When farmers who have lost their lands to climate-change-prompted droughts flee to Europe, she said, they can be dismissed as “economic migrants” with little regard to the environmental injustice that has uprooted them.

That’s unfair, she says: “Everything needs to be looked at in a holistic manner.”

Deirdre Duff, head of communications in Ireland for the environmental non-profit Friends of the Earth, said: “Wealthy countries have caused the climate change that is displacing people from their homes and lands in the global South.”

Sara Althabhaney. Photo by Shamim Malekmian.

In the case of the man from Malawi, whose village was destroyed by floods, the tribunal member said that to accept that the man’s case counted as persecution or serious harm, there would need to be a person or actor causing this persecution or harm.

It is too much of a stretch to say that the degrading treatment or punishment was meted out by people burning fossil fuels in a country far away, perhaps long ago, said the IPAT member. “The causal connection is far too tenuous; the chain of inference, far too long.”

Besides, he said, “anthropogenic climate change” and “climate change ‘simpliciter’” are “scientific theories rather then settled facts”.

Scientists say that suggesting climate change science can’t be relied on because it’s presented as theory not fact misrepresents the way they use the word “theory”, as opposed to “hypothesis”.

“In science, theory pertains to a principle or set of principles that have been convincingly well established,” says a climate primer by a professor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “If the theory of general relativity were ‘just a theory,’ no one’s GPS would work.”

While the tribunal member in the man from Bangladesh’s case says they accept that climate-change-induced flooding had ruined his lands and home, they disputed whether that can amount to serious harm.

Because “like illness”, climate change “is a naturally occurring phenomenon”, as distinct from an act of harm at the hands of either) the state or non-state actors, the decision says.

“There is little doubt that human activity is influencing climate change, but there is considerable debate about the extent to which it is a natural, cyclic phenomenon and the extent to which it is anthropogenic,” the member says.

(The European Commission says that CO2 produced by human activities is the largest contributor to global warming.)

Says the member’s decision: “Insofar as the evidence suggests that human activity is at fault; that would appear to be through gross recklessness rather than through any deliberate or intentional act by State or non-state actors”, so “the effects of climate change – however inhuman or degrading – cannot amount to serious harm.”

“I can’t follow that logic,” says Joe Noonan, an environmental solicitor at the law firm Noonan Linehan Carroll Coffey.

“The reason I say that is if something is foreseeable and predictable consequence of an action then that is sufficient, normally, to prove intent,” Noonan says.

Even if one was to get over that argument, though, Noonan says, “it doesn’t get past the other weaknesses in the law”.

The Refugee Convention is outdated, he says, and its legal void on climate change must be filled.

No Guidelines, No Change

Without legal guidelines it is easy for asylum decision-makers to dismiss climate-related claims, said Kälin, the constitutional and human-rights lawyer in Switzerland, during last week’s webinar.

“There is a temptation for decision-makers to say that’s manifestly unfounded because it’s not one of the reasons covered by the 1951 convention,” said Kälin.

Stephen Kirwan, an associate solicitor at the law firm KOD Lyons, says the law must change.

“There is a lot of stuff that the convention doesn’t cover, like internally displaced people, like they’re not considered refugees for the purpose of the convention,” Kirwan said.

He said the convention needs to include the notion of climate refugees as solid ground for seeking asylum.

“This is a problem that needs to be addressed, and I see difficulties in addressing it through the current protection framework,” he said.

Duff, at Friends of the Earth, said that wealthier countries should also offer financial support to poorer states to combat climate change so that it won’t uproot their citizens in the first place.

“We should support peoples’ right to move – but also their right to stay – in the places where their families, livelihoods and everything they love is based,” she said.

Mfaco, the asylum-seeker and PhD student, says that if countries got together to amend the Refugee Convention to recognise victims of climate change, it’s unlikely they’d find common ground.

“Even when they were trying to reform the EU Directive on reception conditions for asylum-seekers, they had to park that because they couldn’t reach a consensus,” said Mfaco.

“So, opening that for discussions, I foresee chaos,” he says, laughing.

He says it’s possible to recognise climate refugees within the current legal framework without amending the Refugee Convention, even if the law falls short of an explicit mention.

“Remember that membership of a social group does offer the ‘other’ option, so there is room for expansion to include climate refugees in the current framework,” he says.

(The UNHCR guidelines on this clause of the refugee convention give some room to decision-makers to count people as members of a certain social group if they’re part of something that “sets them apart from society at large”. That’s how it sometimes, depending on societal contexts, recognises women, families and queer people as falling under this category.)

But based on his own experience as a queer asylum-seeker, Mfaco says, he has little hope for change.

“In South Africa, I had stones thrown at me, I had somebody spit on me for no reason other than my sexual orientation, somebody who lived down the road where I lived was openly gay and was abducted and murdered for her sexual orientation,” says Mfaco, whose application for humanitarian leave to remain was rejected by the Minister for Justice.

“They said, no to me, so …,” he said.

If you require any further information in relation to this post, please do not hesitate to contact us at stephen.kirwan@kodlyons.ie.

See the original article on the Dublin InQuirer.

Get in touch

Leaders in our field and winners at the Irish Law awards we have proven expertise in immigration and international law, child and family law and personal injury litigation.

Tel: +353 1 679 0780

Email: info@kodlyons.ie